Why You Need Courage for the Attractional-to-Gospel Transition

When you've walked a certain road for a certain length of time, long enough to attract followers who agree with your direction, you will absolutely alienate some — if not many — if you change directions.

My current writing project — scheduled to publish in 2019 from Zondervan — is a book aimed at helping ministry leaders practically, carefully, and wisely navigate the transitioning of their church from the attractional paradigm (with its functional ideology of pragmatism and consumerism) to greater gospel-centrality. One of the central tenets of the book is that ministers leading this change must summon great courage.

They must summon great courage because they will invariably, inevitably lose people. Perhaps a lot of people. Perhaps even fellow leaders.

What you win them with is what you win them to. And if you've won them with attractional programming, you can expect they've been won to it, and thus any strong deviation, even moreso in the direction of gospel-centered preaching and biblically healthy church dynamics, because even those moves can be quite jarring for the uninitiated.

It reminds me, actually, of 1965.

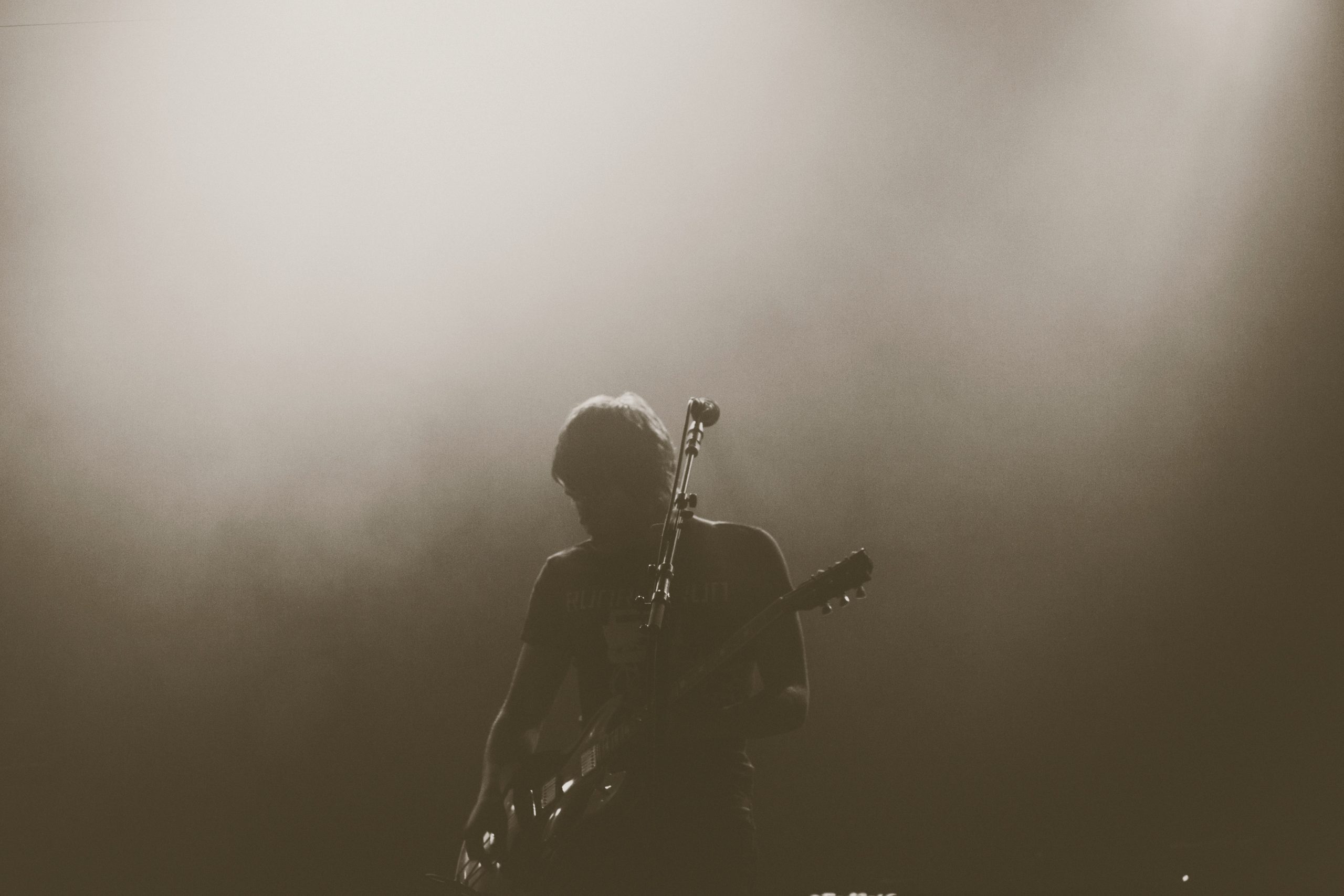

No, I wasn't alive then. I was negative-10 in 1965, but that was the year the great Bob Dylan took to the stage of the Newport Folk Festival and made everybody angry. How? By plugging in his guitar.

Playing electric wasn't new then, of course. And today it's entirely uncontroversial. But the folk scene at the time — as Dylan was ascending to its highest point — favored a kind of musical purity, a singularity, a stripped-down way of presenting truths. And Dylan had garnered acclaim doing just that, performing alone, just he and an acoustic guitar (and harmonica) and a microphone.

Many of his fans had come to equate him with that "traditional" form of expression. So when he took the stage in defiance of expectation, with an accompanying band and 1.21 jigawatts of power — which some said actually overpowered his vocals, their true complaint — it didn't matter how awesome it was, how artistic it was, how Bob Dylan it was.

He changed the direction. And many in the crowd turned on him, loudly booing. (Dylan later returned for an encore and played by himself, with just an acoustic guitar.)

One music historian said that at Newport, Dylan electrified one half of the crowd and electrocuted the other.

This will happen if you set aside the inspirational pep-talks, pragmatic chit-chat, therapeutic aphorisms and preach the word, with Christ and his finished work as the main feature. You will electrify half your crowd who didn't know what they were missing and you will electrocute the others, who may feel confused, perhaps even betrayed.

I've talked to a few pastors of larger churches who have sought to make the transition to greater gospel-centrality. Not many even try. These brave souls end up seeking to pastor disillusioned souls, angry souls. They unfortunately see many leave. The bravest keep going.

If you are pondering what it might mean to "change the game" in your preaching and ministry aims, to put Christ and the gospel at the center, don't be afraid. You will get booed. But it's just because they don't see what you see. One thing that makes Dylan Dylan is his refusal to cater to the crowds, to simply play the music, to let the song be the feature, not himself. Not to strain the analogy too much, but let's let the gospel be the feature of our churches and let the chips fall where they may.

Maybe this Sunday is your "Newport 1965" Sunday. It's a Sunday we'll be talking about 50 years from now. That "relevant" stuff you've been doing? We'll forget about it next month.

Pragmatism goes with the times, and to go with the times, as C.S. Lewis said, is to go where all times go. The gospel, however, goes to 11.