Lemuel Haynes is one of the most significant figures in American (and Church) history that most people have never heard of. [1] Born July 18 in 1753 the son of a black man and a white woman, Haynes was abandoned by his parents in the home of a family friend who sold the infant Haynes into indentured servitude. By the providential hand of God, however, young Lemuel was placed into a devoutly Christian home, where by all accounts, including his own, he was treated as a member of the family.

Growing up in colonial-era Massachusetts, Haynes worked hard and studied hard, proving himself quite adept at intellectual pursuits despite mostly needing to self-teach. He has affectionately been called a “disciple of the chimney-corner,” as that is where he would spend most evenings after work reading and memorizing while other children were out playing or engaging in other diversions.

Haynes’s commitment to theology began in that chimney corner, and eventually he was born again. Not long after his conversion, he turned his followship of Christ and his intellectual bent into a serious endeavoring after writing and preaching. An oft-told anecdote about Haynes concerns a scene of family devotions at the Rose household, where he was indentured. Given his adeptness at reading and reading and his deep concern for spiritual matters, the Rose family would often ask Haynes to read a portion of Scripture or a published sermon. One night, Haynes read one of his own without credit. At the end, members of the family remarked at its quality and wondered, “Was that a Whitefield?

“No,” Haynes is said to have replied. “It was a Haynes.”

The few sermons we have of Lemuel Haynes prove him to be an exceptional expositor in the Puritan tradition, similar to an Edwards or Whitefield, simpler than the former but more substantive than the latter. And yet, what Haynes may lack in eloquence compared to his contemporaries, he more than makes up for in biblicism and applicational insight.

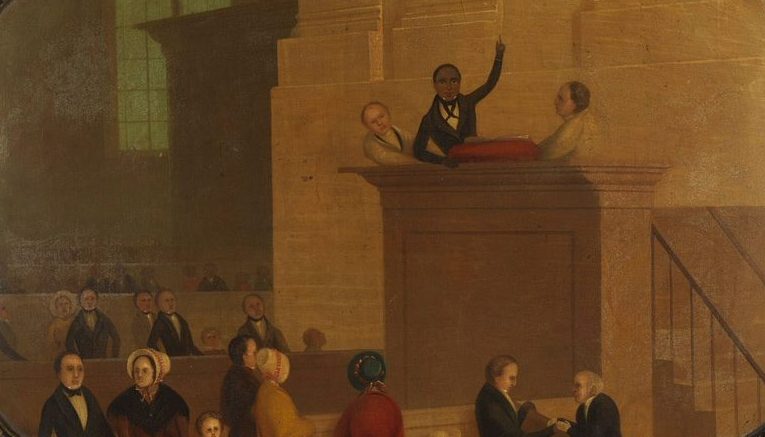

Officially licensed to preach in 1780 by the Congregational Association, Haynes soon thereafter preached his first public sermon (on Psalm 96). Ordained in 1785, Haynes later received an honorary Master of Arts degree from Middlebury College.

Haynes was a theologian of the New Light school, or New Divinity. He was also a patriot—he enlisted in the Continental Army in 1776 and marched with colonial troops to Ticonderoga, among other assignments. His military service was no mere distraction or aimless diversion but representative of his heartfelt affection for the American experiment. He was described thusly by his first biographer, Timothy Mather Cooley: “In principle he was a disciple of [George] Washington.”

These two most significant truths about Haynes’s philosophical convictions—his Puritan theology and his American patriotism—would prove his two most powerful drivers in his life and ministry. He did not see these viewpoints as contrary at all, but rather complements. Haynes believed, for instance, that the abolition of slavery was not just a true move of human righteousness in reflection of the real belief in the Providence of God but also the truest form of faith in the American experiment.

And what kind of preacher was Lemuel Haynes? Biographer Timothy Mather Cooley remarks that “Never did he wait to inquire whether a particular doctrine was popular. His only inquiries were, ‘Is it true? Is it profitable? Is it seasonable?’”

Thus, in Haynes’s work, we may have a model for preaching to divisive politico-cultural contexts today. While we no longer struggle with legalized slavery in America, we are nevertheless still torn over political and cultural issues of justice, human relations, and related concerns. At once a Christian may feel drawn toward a sub-gospel approach to justice issues, in which doctrine takes a back seat to human concerns of flourishing and liberation, or equally drawn toward a non-applicational theology that divorces the gospel from its social implications.

Right now in American evangelicalism we are experiencing a great balkanization, some of which involves fracture lines along issues of social justice or racial reconciliation. One would think we’d be beyond the concerns addressed in more rudimentary terms in colonial America. But here we are. And our preaching must take the timeless Word into our troubled world.

A Concern for Justice

The theme of justice appears in Haynes’s earliest writing, including a poem he wrote in 1775 on “The Battle of Lexington,” in which we find these somber lines, upon the pondering of soldiers’ tombs: “We rather seek these silent Rooms / Than live as Slaves to You.”

Haynes’s earliest known sermon was that familial homily on John 3:3. With its simple division of commentary and application, the astute reader can see how in the application stage especially, Haynes is already thinking of the import of the gospel to the social contexts of those reborn. “Have we got that universal benevolence which is the peculiar characteristic of a good man?” he asks.

Elsewhere in that sermon, he connects love for God with benevolence to man, which is the essence of biblical justice. This earliest sermon of Lemuel Haynes demonstrates his early infatuation with the impact of the spiritual kingdom of Christ here in this world.

The later Haynes sermon titled “The Prisoner Released” was inspired by a peculiar “true crime”-type episode of which Haynes found himself at the center. This sermon has some of Haynes’s most direct words to a Christian congregation on Providence and justice. For instance, consider the import of this claim: “Every decision is dictated by infinite wisdom and infinite goodness: he can by no means clear the guilty or condemn the innocent. ‘God will judge the people with perfect equity, and justice and judgment are the habitation of his throne,’ Psal. lxxxix.,14.”

As justice is discussed, however, the focus is always on the cross. Haynes even contrasts human justice with the Lord’s. Haynes writes, “The emancipation granted by human courts is only a reprieve of the body for a years, months, or days—perhaps hours or moments . . . But the act of the Almighty frees the soul from the terrors of the first and second death.”

Justice is also the largest concern of Haynes’s (now) second most known written work, the essay “Liberty Further Extended.” Richard Newman has called it “the most important discovery of Black writing in this century.”[2] In this remarkable early political discourse, Haynes argues on the grounds of both biblical theology and natural law that the enslavement of the African and the employment of slavery in the American colonies is a sin against both God and mankind and ought to be ended.

In it Haynes writes: “Liberty is a Jewel which was handed Down to man from the cabinet of heaven.” In this essay, Haynes argues that “Liberty, & freedom, is an innate principle, which his unmoveably placed in the human Species” and that “those privileges that are granted to us By the Divine Being, no one has the Least right to take them from us without our consen[t].”

Haynes further cites the Golden Rule as the purest conception of a system of law and argues that the proliferation of slavery taints the potency of Christian mission. It is an inelegant essay in style (and grammar), but Haynes’s elegant theology shines through as he declares that human beings are pronounced innately free by “the immutable Laws of God, and indefeasible Laws of nature.”

In his lesser known political essay, “The Influence of Civil Government on Religion,” Haynes’s interest in justice marches on. “He that ruleth over men must be just,” he writes, “ruling in the fear of God.” He also goes on to explicitly connect divine justice to civil justice and apply the Scriptures to the politico-cultural context of the time.

While these latter writings from Haynes are not sermons, nor are they directly written for an explicitly religious audience, the doctrinal foundation of “Liberty Further Extended,” and even its pointed approach to persuasion, would prove recurring features of Haynes’s sermons. The major themes of Providence and justice are here in bald form, even as they would later appear latent in his preaching.

In his sermon “Divine Decrees,” Haynes makes some of his most explicit connections between divine righteousness and social justice. In his concluding remarks in the sermon, he writes:

There is no external duty that is spoken of in Scripture that is so evidential of our love to God, as imparting a portion to the necessities of the souls and bodies of men. It will be publicly held up at the day of judgment, as a test of the sincerity of the righteous:—“For I was an hungry [sic], and ye gave me meat.”

A Passionate “Right-Sizing” of Politics

How strong was Haynes’s interest in political matters? This is a subject of some debate even today.

Cooley metions that Haynes indicated a disinterest and even distaste for politics, reprinting a letter in which Haynes writes: “Dissensions about politics have had an unfavourable influence on religion, as they have greatly tended to alienate the affections of the people from each other, at least in many towns in the state.” In a subsequent letter, he mentions that he feels a reluctance to mention political subjects in his sermons, and still later that he believed “political distraction . . . has extinguished the flame” of revival in his church.

Haynes seemed never overtly political in his sermons. However, he did not seem to eschew politics at all. He merely seemed to make a conscious effort to devote his explicitly political remarks to explicitly political arenas. In addition to his published work (against slavery and the like), there are numerous quips and second-hand recollections regarding his political viewpoints. In his foreword to Saillant’s historical analysis of Haynes, Mechal Sobel notes, for instance, Haynes’s opposition to the War of 1812, calling it “unjust.”[3]

But Haynes’s political thinking seemed less a diversionary interest in power or sport, but part of his thorough-going concern for justice. It pervades his sermons, his essays, and his letters. He seemed to believe that no matter his audience, the politico-cultural context of his day required some instruction in how God’s holiness impacts our ways with each other.

Haynes and Racism

Richard Newman, whose curious “bio-bibliography” of Haynes includes a biographical sketch that gathers some important evidential reminders that to be black in early American history, no matter the political or cultural context of your immediate surroundings, was inevitably to suffer racism. As an example, Mechal Sobel notes the responses to Haynes’s famous homiletical riposte to the universalist Hosea Ballou:

There were several published attempts to answer Haynes’ sermon, but these are of interest now more for the racist aspect of their polemic than for the theological importance of their arguments. David Pickering . . . spoke of Haynes, “between the shade of whose mind, and whose external surface, there exists such a striking similarity,” and explained the joke in a footnote: “The author of the discourse in question is a coloured man.” In Joseph H. Ellis’ A Reply to Haynes’ Sermon, the devil was pointedly referred to as “this black gentleman,” “his complexion is as dark as ever,” etc.[4]

Scholar Richard Brown situates Haynes in the midst of a “complexity of whites’ attitudes toward blacks in the New England of the early republic.”[5] That is Haynes’s politico-cultural context: a complex society of conflicting convictions about non-whites. It was unavoidable for him in lily-white Vermont. Brown even mines the story of Haynes’s courtship and eventual marriage to his wife, who was white, for evidence of the racial animus at work in Haynes’s own life.

Historian John Saillant examined Haynes’s views of divine Providence in relation to the slavery issue and claims that Haynes, “[i]n decrying the slaveholders’ and slave traders’ selfishness,” he was merely “echoing” his teachers in the New Divinity. In the end, Saillant sees in Haynes a sort of proto-Liberation Theology, which is unfortunate given Hayne’s theological commitments. His gospel is not a social gospel, but it is certainly a gospel with social dimensions.

Conclusion

How might we best preach to our divisive, volatile, polarizing politico-cultural contexts, and what can Lemuel Haynes teach us about that?

I believe there is a great opportunity here to do a great service to church history and also to the work of preaching the gospel and the mission of God in the world. Lemuel Haynes’s writing is indeed a great resource to this end. He was a black preacher in a white world.

Haynes was certainly a man of his time, and he knew that his times called for a certain kind of preaching. Indeed, he knew that all times call for the gospel-centered kind of preaching. And yet applying the eternal gospel to the particular times was of keen interest. As Saillant writes, “His sense of blackness was articulated in a drive to unearth historical and theological meanings pertinent to the situation of blacks . . .”[6] He puts it in broader perspective elsewhere thusly: the “antislavery stand became part of a larger pattern of social protest against the modernizing and liberalizing tendencies of late eighteenth-century New England.”[7]

Our contexts might be different. But our concerns should be the same. What does the Scripture say about this context? What does the Scripture say, timelessly, to these times? We ought to ask of our own preaching what, according to Timothy Mather Cooley, Haynes asked of his own: “Is it seasonable?”

[1] Historian Richard Newman unabashedly called him “the most significant Black man in America prior to the emergence of Frederick Douglass.”

[2] Richard Newman, Lemuel Haynes: A Bio-Bibliography (New York: Lambeth Press,

1984), 4.

[3] Mechal Sobel, “Foreword,” in Black Preacher to White America: The Collected Writings of Lemuel Haynes, 1774-1833, ed. by Richard Newman (Brooklyn: Carlson, 1990), ix.

[4] Ibid., 14.

[5] Richard D. Brown, “‘Not Only Extreme Poverty, but the Worst Kind of Orphanage’: Lemuel Haynes and the Boundaries of Racial Tolerance on the Yankee Frontier, 1770-1820,” The New England Quarterly 61, no 4 (December 1998), 504.

[6] John Saillant, Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes, 1753-1833 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 20.

[7] John Saillant, “Lemuel Haynes and the Revolutionary Origins of Black Theology, 1776-1801,” Religion and American Culture 2, no 1 (Winter 1992), 82.