Was there anything distinctively Baptist about Henry’s political thought? The answer is yes, and it is focused on the first freedom: religious liberty.

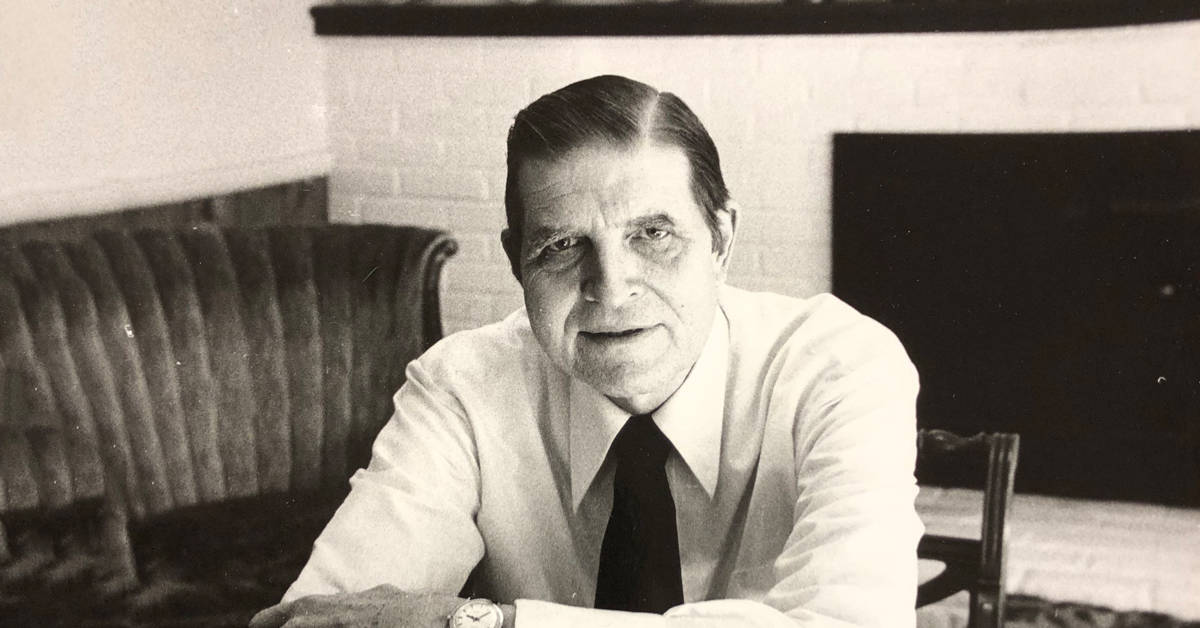

Carl F. H. Henry was a Baptist. That might seem like an unnecessary remark in a volume devoted to Baptist political theology, but with Henry it is a point worth making. During his time at Wheaton College, he was convinced of Baptistic views and would be affiliated with Baptist churches and institutions for the remainder of his life.[1] The Baptist understanding of church and state was one of the influences that drew him to Baptist distinctives.[2] But while he made no reservations about his Baptist identity, his “most critical involvements have been outside denominational life.”[3] He is usually recalled as an Evangelical rather than a Baptist and for understandable reasons. He nearly always referred to the “evangelical church” in the singular, “not referring to any particular denomination but to all conservative Protestants committed to the formal and material principles of the Reformation.”[4] This was undoubtedly due to his role as theologian-at-large for a conservative interdenominational evangelicalism.

But how did Henry as a Baptist think about politics? Henry adopted the Baptist understanding of religious liberty, and he articulated a distinctly Baptist version of the first freedom throughout his life.[5] This view originated from the Bible and was filtered through his kingdom framework, stressing the two spheres believers inhabit and concluding that the state ought not dictate to the church and the church ought not overrun the state. For Henry, the church should seek in good faith to evangelize her neighbors but should never “impose upon society at large her theological commitments.”[6] However, because God “wills the state as an instrumentality for preserving justice and restraining disorder,” Christians should engage in political affairs, vote faithfully and intelligently, and seek and hold public office.[7] The church should respect the authority granted to the state by God, but not as a fire wall against any prophetic proclamations. Further, religious liberty provides space for irreligion (though, as we have seen, Henry believed nobody is truly irreligious) as well as those of other faiths. Henry believed evangelicals should “earnestly protect” the freedom of all people—“be they Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, Confucian, or whatever—even while we passionately proclaim to all the gospel of Christ.”[8] While Henry’s intellectual efforts were claimed by some among the Religious Right, this was a key place where he distanced himself from the movement. He criticized its tendency to elevate Christian freedom over and above religious freedom and to be less-than interested in religious freedom “across the board” for people of various and differing faith traditions.[9]

Beyond Henry’s view of religious liberty, other Baptist influences can be discerned in his thought, especially in the area of ecclesiology. While Henry has been critiqued for neglecting the locality of the church (due to his scant attention to polity and ordinances), he did appeal to the local church in the construction of his political theology.[10] Because Henry believed “public virtue depends on private character, and private character emerges from convictions about the ultimately real world,” he began at the local level by emphasizing the church’s ministry in the formation of believers who would conduct themselves politically in ways that honored transcendent realities.[11] For Henry, pulpits and pews were integral to Christian political theory—what flowed downstream into political activity, positive or negative, was contingent on ecclesiological faithfulness. As Jonathan Leeman states, “The church’s political nature begins with its own life—with its preaching, evangelism, member oversight and discipline.”[12] Henry recognized and appreciated this in his articulation of political theology. While Baptists are not alone in taking seriously the responsibilities of church membership, one can appreciate Henry the Baptist in how he related church discipline to civil life: “Through government of its own members, the Church indirectly promotes the welfare of society as a whole. . . . When the Church requires her membership to practice Christian principles in everyday life it unavoidably touches upon many areas of conduct subject also to civil legislation.”[13] Henry connected the effectiveness of a proper Christian political vision with the spiritual vitality of the individual and, by extension, the formative role of the covenant community.

Peter Heltzel sees Henry as a “prophetic Baptist” because of Henry’s radical reframing of Baptist cultural engagement.[14] Heltzel gives three reasons to justify this classification: While operating from the Baptist stream of theology, Henry championed the dignity of all people, demonstrated the best of the reformist and revivalist traditions, and rejected theocratic tendencies.[15] And while one wonders whether Henry was as much a “prophetic Baptist” as he was simply a consistent one, the point remains: his Baptist convictions informed his political theology, and Heltzel’s emphasis reminds us of this.

Henry was a consistent Baptist, but he was not an altogether unique Baptist in his conception of political theology. Does he offer anything fresh to Baptists today beyond what has already been said? Certainly, the biblical and theological underpinnings of his political theology remain applicable. The theological intentionality that characterizes his work deserves continued emulation. His engagement with alternate views equips modern readers to understand other political options. But Henry offers more, and this is owing to his historical context.

Henry wrote amid “breathtaking changes in the human experience.”[16] He witnessed massive upheaval in the shared societal assumptions of the nation. While every generation is forced to address new developments, the mid-twentieth century saw a titanic shift in how people thought about every aspect of life. From the discarding of traditional sexuality to secular encroachment in education to new forms of media and entertainment, these years marked a watershed in the life of the nation, and Henry addressed many of these changes through a theological lens and a Baptist emphasis on religious liberty.[17]

Baptists face similar challenges today. While Henry’s articulation of Baptist political theology is not unique to him, the intensity with which he applied it was new, and it is here that modern Baptists can find an ally and guide as they navigate an era still grappling with these issues. Henry’s work on political theology remains a valuable tool, especially because of the kinship between his cultural day and ours.

[1] Carl F. H. Henry, “Twenty Years a Baptist,” Foundations 1 (January 1958): 46–47.

[2] Henry, 47.

[3] R. Albert Mohler Jr., “Carl F. H. Henry,” in Theologians of the Baptist Tradition, ed. Timothy George and David S. Dockery (Nashville: B&H, 2001), 292.

[4] Timothy George, “Evangelicals and Others,” First Things 160 (February 2006): 19.

[5] See Henry, The Christian Mindset in a Secular Society, 63–80.

[6] Carl F. H. Henry, Christian Countermoves in a Decadent Culture (Portland: Multnomah, 1986), 118.

[7] Henry, 118.

[8] Henry, The Christian Mindset in a Secular Society, 79.

[9] Carl F. H. Henry, “Lost Momentum: Carl F. H. Henry Looks at the Future of the Religious Right” Christianity Today (September 4, 1987): 31.

[10] See Russell D. Moore, “God, Revelation, and Community: Ecclesiology and Baptist Identity in the Thought of Carl F. H. Henry,” Southern Baptist Journal of Theology 8, no. 4 (Winter 2004).

[11] Henry, Has Democracy Had Its Day?, 41.

[12] Jonathan Leeman, Political Church: The Local Assembly as Embassy of Christ’s Rule, Studies in Christian Doctrine and Scripture (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2016), 52.

[13] Henry, Aspects of Christian Social Ethics, 79.

[14] Heltzel, Jesus and Justice, 76.

[15] Heltzel, 76.

[16] George Marsden, The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s and the Crisis of Liberal Belief (New York: Basic Books, 2014), xv.

[17] In addressing such issues, Henry’s practice was to offer a prophetic “no” to issues clearly contrary to Scripture, but not a clear “yes” to specific policy proposals. This was likely due to his reticence to intertwine church and state and to one of the editorial principles that guided his work at CT: “The institutional church has no mandate, jurisdiction, or competence to endorse political legislation or military tactics or economic specifics in the name of Christ.” See Richard J. Mouw, “Carl Henry Was Right,” Christianity Today (January 2010): 32. This hesitancy to offer specific critique or endorsement of legislation became a point of contention for some of his contemporaries who wanted to see stronger engagement with direct policy matters from one of evangelicalism’s chief thinkers. See Lewis B. Smedes, “The Evangelicals and the Social Question,” Reformed Journal 16 (February 1966): 9–13.

Editor’s Note: This article is taken from Baptist Political Theology and used by permission of B&H Academic. The book is now available everywhere Christian books are sold.