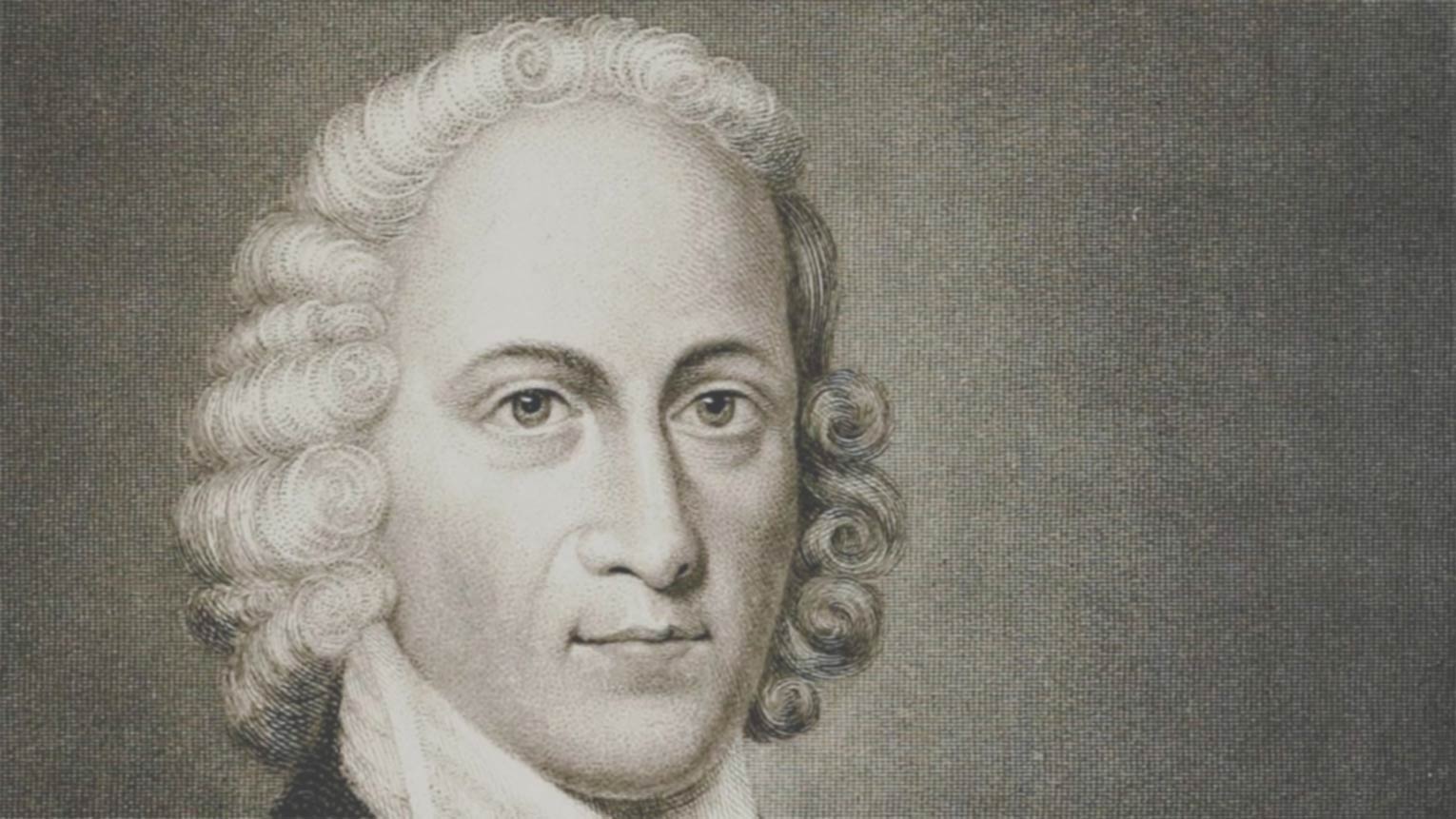

Early in my twenties, I read Jonathan Edwards's “Resolutions,” a display of intent toward holiness written by a man desiring to please God with his life. I read the list over and again, taking in his precisely crafted hopes. Then I made my own list, copying some of Edwards’:

“Resolved, to live with all my might while I do live.”

“To take advantage of every hour given to me and to count it as grace.”

“When I sin, to recall the nature of heart and thought that led me from temptation to action and away from God.”

And the list grew over the years. With each new volume of lined manila pages, I traced my resolutions once again.

In Formed for the Glory of God: Learning from the Spiritual Practices of Jonathan Edwards, Kyle Strobel juxtaposes the elder and younger Edwards, helping me see the work of grace in my own heart. Strobel quotes Edwards:

“Though it seems to me, that in some respects I was a far better Christian, for two or three years after my first conversion, than I am now; and lived in a more constant delight and pleasure: yet of late years, I have had a more full and constant sense of the absolute sovereignty of God, and a delight in that sovereignty; and have had more of a sense of the glory of Christ, as a mediator, as revealed in the Gospel.”

My professor in seminary asked us to consider this scenario:

“Say I have a man whose besetting sin is sleeping around. On average, he is sleeping with 30-40 women a year. The Lord saves that man, and we walk together as brothers. During the next year of his life, he sleeps with three women. Do you condemn this man? Do you doubt his salvation or his understanding of Christ’s work? Think of the standard to which you hold him. If it is holiness, no one has met that, save Christ. If it is the progressive and saving work of the Spirit—then look at how much his life has changed from where he started.”

Talk about throwing a wrench into this church-kid's world!

A worldview like that—a worldview of incremental holiness—is one that recognizes dependence, inability and false righteousness. The saved man’s life is changed, and he is still in need of grace. To think of where I have come from and where I am now—gratitude grows with every dip, every bend, and every fresh recognition of grace.

Edwards goes on:

“I have a vastly greater sense, of my universal, exceeding dependence on God’s grace and strength, and mere good pleasure, of late, than I used to formerly have; and have experienced more of an abhorrence of my own righteousness. The thought of any comfort or joy, arising in me, on any consideration, or reflection on my own amiableness, or any of my performances or experiences, or any goodness of heart or life, is nauseous and detestable to me. And yet I am greatly afflicted with a proud and self-righteous spirit; much more sensibly than I used to be formerly.”

The elder Edwards is aware of his frame and open with his need in a way the younger was not. His fully formed voice is worth hearing, one tempered by grace—sweeter, humbler, more dependent. His heart moves from a list of moral action to sitting at Christ’s feet, and he calls others to sit beside him.

My professor continued:

"What happens when I have jumped through all the sanctification hoops of those I trust, and it doesn't work? What do I do? The mark of a Christian is his affections and desires, not his momentary lapses. Not that he does well, but that he knows the pit out of which he was dug, and knows where to go for cleansing when he falls back into it."

Maturity for Edwards, and for us, is greater dependence upon the person and work of Christ. Grace takes a believer and gives them eyes to see themselves in light of who Christ is “much more sensibly than…formerly.” Incremental holiness takes time. Sober knowledge of self meets deep trust in the person of God, and we trust that in our moments of self trust, our falls and failures, He is good.

© 2013 The Village Church, Flower Mound, Texas. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Originally published at https://www.thevillagechurch.net/the-village-blog/edwards-for-everyday/