According to the Wycliffe Global Alliance, only 2,932 of the approximately 7,000 languages have at least some of the bible; this leaves 3,955 languages without access to Scripture. Because “faith comes from hearing, and hearing from the word of Christ” (Rom 10:17), the translated word of God is essential!

The Benefit of Multiple English Translations in Bible Study

With so many peoples globally having no Scripture in their heart language, English speakers should be deeply grateful to God for the plethora of solid Bible translations that we have. Whether you know the biblical languages or not, several good English translations will serve you well in studying the Bible and teaching. When studying Scripture, those who don’t know the original languages and who rely fully on translations are at the mercy of the translators, who themselves have made interpretive decisions about the meaning of the Hebrew or Greek text. If you only use one translation, you are even more limited in your ability to identify and evaluate interpretive options. With respect to teaching, your audience could be using over a dozen different contemporary English translations, many of which will differ to greater or lesser degrees. As such, the more you familiarize yourself with the various translations, the more confident you’ll be that you have made the best exegetical choices and the more prepared you’ll be to answer questions as they arise.

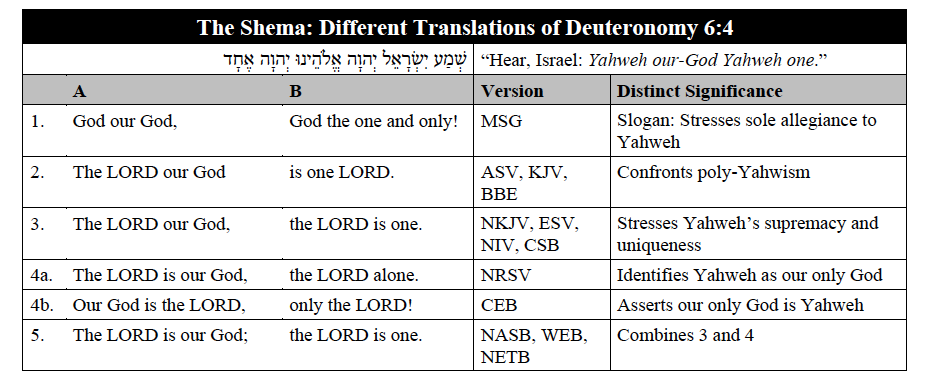

Consider, for example, some various renderings of the Shema in Deuteronomy 6:4.

A quick glimpse at these translations identifies some key questions that you probably would have missed had you only looked at a single translation. For example, how should we understand the structure of the Shema? Is it a verbless slogan (#1), a single sentence (##2, 3, 4), or two sentences (#5)? This decision affects our understanding of the whole. Also, what is the meaning of Yahweh’s oneness? Is this oneness bound up in God’s nature (##2, 3, 5), or does it address the nature of our allegiance (#4)? If you are slated to teach this passage, comparing the translations lets you know that you have some important exegetical work to do in order to rightly understand the text’s message. Had you only used the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) or New American Standard Bible (NASB), you would have never seen these options.[1]

For the purposes of Bible memorization and consistency in teaching, using a single quality translation is best. In my sphere of ministry, the most common are the New American Standard Bible (NASB), English Standard Version (ESV), New International Version (NIV), and Christian Standard Bible (CSB), but there are other solid options. For the purpose of Bible study, however, multiple well-chosen translations will supply the interpreter greater awareness of exegetical options and the greatest preparedness for ministry in the English-speaking world.

Engaging Different Translations and Translation Theories

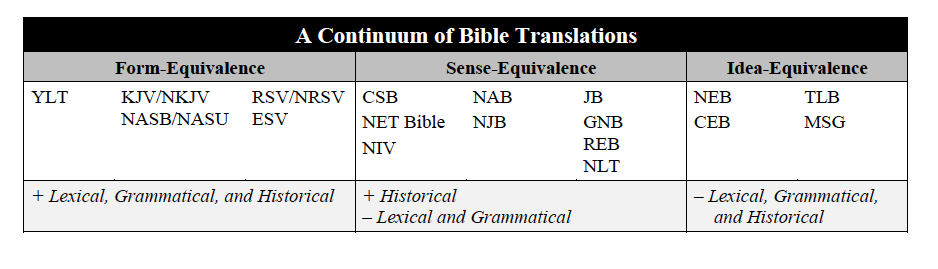

Bible translations differ on whether they are form-, sense-, or idea-driven and to what degree they are gender-inclusive. Different translation theories actually stand behind the various versions, creating a continuum of equivalence (displayed below) based on how they handle lexical, grammatical, and historical correspondences. Lexical correspondence relates to how closely translators attempt to render single words in the source text into individual words in the target language. Grammatical correspondence addresses how closely the translators align word-order and syntax in the original language with word-order and syntax in translation. Finally, historical correspondence concerns how closely the translators retain the factual and cultural elements connected with the biblical times. You may think that the more rigorously tied a translation is to lexical, grammatical, and historical correspondence, the more faithful the translation will be to the original. However, liberal-versus-conservative theology does not appear to play a role in which translation theory scholars prefer. Each of the various approaches have their own strengths and weaknesses, and often distinct purposes drive the choice of one approach to another.

Form-Equivalence

Versions that strive for form-equivalence try to retain correspondence of words, grammar, and history as much as possible between the original and receptor language. Some people refer to these as “literal” translations. Such terminology is a misnomer seeing as no two-languages enjoy one-to-one correspondence in everything, and[NM1] often, the English equivalent requires a more dynamic rendering to actually capture the sense of the original in the receptor language. The older Young’s Literal Translation (YLT 1862) failed to recognize this point, assuming that complete grammatical and lexical equivalence was always possible. The result was that the translation regularly disregarded the normal structures of English, making the text almost nonsensical.

Two of the best form-driven translations are the New American Standard Bible (NASB 1995) and the English Standard Version (ESV 2016). The former is especially helpful when trying to track an author’s flow-of-thought because it renders almost all the connecting words, which serve as signals for text-structure. This type of translation is the least interpretive, and because of this, I choose a formally equivalent translation as my primary English version for Bible study. However, while form-driven translations can be understandable, they often use cumbersome English, which requires the teacher to clarify meaning more often. The ESV strikes a helpful balance between form and meaning, but in the Old Testament[NM2] it fails to translate many of the connectors, making it more difficult to use for tracing an argument.

Sense-Equivalence

Sense-equivalent translations like the New International Version (NIV 2011) and New Living Translation (NLT 2004) provide beautiful and meaningful contemporary English. They seek functional/dynamic correspondence, retaining the historical-factual features of the text and capturing the meaning of the Hebrew and Greek, while not hesitating to translate the words, grammar, and style into common English words, structures, and idioms. More interpretation takes place here, but if the translators do their job well, the result is a clear and faithful rendering of God’s word that can serve everyone, especially those who need more help in grasping the meaning of the Bible’s propositions.

Where there is greater interpretation in translation, however, there is also more opportunity for the preacher or teacher to disagree with the translator’s choices. Furthermore, translations that seek sense-equivalence often fail to represent important text features like connectors or discourse-markers. Without these structural signals, the interpreter cannot track the author’s argument as easily, so he is further distanced from the ancient book.

Idea-Equivalence

Translations that seek idea-equivalence include The Living Bible (TLB 1971) and The Message (MSG 2002). It is really better to call such versions paraphrases, since they only strive to convey the concepts of Scripture with little attempt to retain lexical, grammatical, or historical correspondence. These can contemporize God’s word, but they are less helpful for study or teaching because they have distanced themselves so far from the original.

Translation Theories at Work

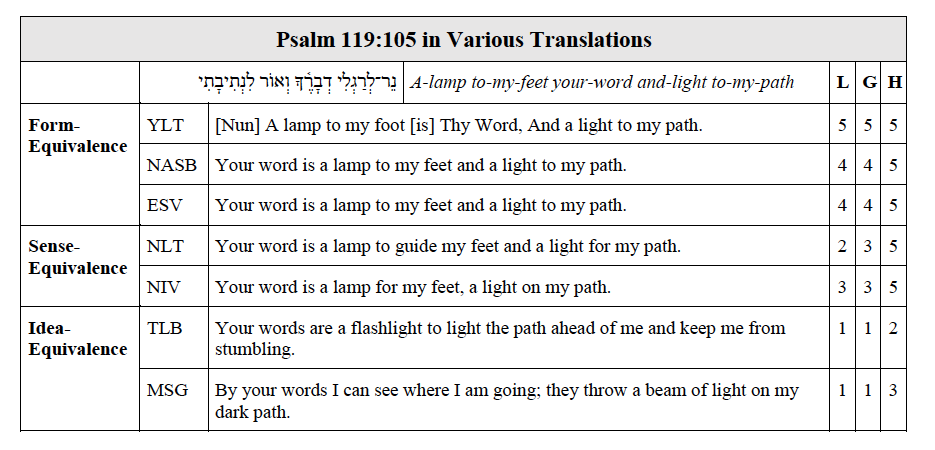

As an example of the equivalence continuum at work, compare the following renderings of Psalm 119:105 in Youngs Literal Translation (YLT), New American Standard Bible (NASB), English Standard Version (ESV), New Living Translation (NLT), New International Version (NIV), The Living Bible (TLB), and the Message (MSG). The right-hand columns identify how closely the translation corresponds to the Hebrew with respect to lexical (“L”), grammatical (“G”), and historical (“H”) features. The number “5” represents the highest level of correspondence, and “1” represents the least.

Surveying the translations shows that some vary drastically, but others not so much. With respect to the form-equivalent translations, with the word “Nun” YLT notes upfront that Psalm 119:105 is part of an alphabetical acrostic and falls in the section where the poetic lines begin with the Hebrew letter נ (“Nun”). It identifies the verse as a verbless clause, placing “is” in brackets, and it retains the singular Hebrew “foot.” It maintains Hebrew word order and offers an equivalent for every Hebrew linguistic form, but it does so at the cost of making the English rough. The NASB and ESV, while having smoother English, still preserve the conjunction “and” (וְ) and the repeated preposition “to” (לְ). But they also reverse the word order at the front of the first clause, allowing for more natural English, and they read the singular “foot” collectively as “feet.” While they fully maintain historical correspondence, they somewhat minimize lexical and grammatical correspondence in order to communicate more effectively in English.

As sense-driven translations, the NLT and NIV attempt to make the English even more flowing. The NIV also renders “foot” as “feet,” but it drops the conjunction and changes the second preposition, probably for stylistic variation. The NLT retains the conjunction, alters the second preposition, and then adds the dynamic infinitive “to guide” for clearer comprehension. Both the NIV and NLT retain full historical correspondence, but both are even more willing than the ESV to drop lexical and grammatical correspondence to be readable. Whether they sacrifice literalness is debatable.

The mere fact that both TLB and MSG have more words identifies that these idea-equivalent translations are rendering concepts, not words or phrases. The TLB is a complete paraphrase that bears little if any lexical, grammatical, or historical correspondence. Was there a “flashlight” in the Old Testament period? It changes God’s “word” to “words,” and it transforms both clause-structure and word-order. As for the MSG, it too is a complete paraphrase that creates two independent clauses and loses nearly all lexical and grammatical correspondence, while retaining historical equivalence.

Every theory of Bible translation has strengths and challenges. We must judge the quality of a translation not simply on its faithfulness to the Hebrew or Greek original but also in light of its target audience and communicative purpose. A more sense-driven translation like the NLT may benefit more the public reading of Scripture since it often captures the meaning of the original in fresh, evocative ways. Idea-equivalent versions can be helpful for those who have little to no exposure to the Bible and/or have a limited understanding of English (e.g., children and individuals learning English).

For personal study and lesson preparation, I encourage you to interact with at least three versions that stand at different points along the equivalence-continuum. My preferences are the NASB, ESV, and NIV. If you don’t know Hebrew, the more form-based translations will ensure that you spot more of the connectors and discourse-markers so as to better track the author’s intended thought-flow. But engaging more dynamically equivalent translations can also help you better grasp the sense of given clauses and phrases. In teaching situations, be sure to know the main translation your audience is using.

Note: This post adapts material from “Chapter 4: Translation” in DeRouchie’s How to Understand and Apply the Old Testament, 157–77.

[1] In chapter five of my book, I discuss some reasons for why I prefer option three above. See Jason S. DeRouchie, How to Understand and Apply the Old Testament: Twelve Steps from Exegesis to Theology (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2017), 215–20.