In God’s wisdom, he chose to give us his Word in a book shaped by words. Words often carry a range of meanings, dependent on the context. If I say “trunk,” many different images may come to mind: (1) the main woody stem of a tree, (2) the torso of a person or animal’s body, (3) the extended nose of an elephant, (4) a large box with hinged lid, or (5) the storage compartment located at the rear of a vehicle. It is important to note that a word will not bear all of its possible meanings each time it occurs.

Because word-meanings can overlap, in any given context an author could choose different words to communicate the same reality. Even when a certain word is not used, the concept may still be present. Because the message of every passage of Scripture is dependent on the meaning of words, phrases, and concepts, knowing how to grasp such meaning is vitally important for interpretation. This post will overview the key tools, principles, and process for doing word and concept studies in the Old Testament for those without knowledge of Hebrew.

An Overview of Concordance, Lexicons, and Theological Wordbooks

We begin with the tools of the trade for word and conceptstudies. There are three main tools: concordances, lexicons, and theological wordbooks.

1. Concordances

A Hebrew concordance is the most important tool in a word/concept study toolbox. A concordance lists all instances of a word or phrase within a given Testament, usually followed by a sampling of its use in specific contexts. Concordance searches are most efficient and detailed when done electronically, using tools like Accordance or Logos Bible Software. For those without knowledge of Hebrew preferring print editions, the best option is Kohlenberger and Swanson’s The Hebrew-English Concordance to the Old Testament (Zondervan, 1998). This resource is especially useful, for it is linked to the Hebrew text (and Strong’s numbers) but all the Scriptural translations are from the NIV. You should learn to use a Hebrew word-based concordance like those above because concordances that are based on English word searches will miss all occurrences of the Hebrew word that are translated differently in other passages.

2. Lexicons

A lexicon is similar to a dictionary. A lexicon lists the words of a language, usually in alphabetical order, and gives their range of meaning through equivalent words in a different language. In Hebrew lexicons, specific biblical references usually accompany the word glosses (i.e., possible meanings), allowing the lexicon to serve both as a dictionary and a sort of concordance. Lexicons save the interpreter time, and they are essential for exegesis. Nevertheless, know that lexicons are fallible resources. They principally aim to list a word’s possible range of meanings, so the interpreter must must evaluate every word use in context in order to decide which meaning best fits. The best lexicon for those without knowledge of Hebrew is Mounce’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words (Zondervan, 2006). Unlike the older Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words (1939), Mounce’s dictionary builds upon the best of contemporary evangelical scholarship and employs both the Strong’s and Goodrick/Kohlenberger (G/K) numbering systems. The G/K system is supplanting Strong’s as the standard instrument for identifying Hebrew and Greek words, for the system itself is grounded in a better understanding of homonyms (when two different words are spelled the same but have different meanings). If you know the number associated with a Hebrew or Greek word, you can find a definition that includes a word’s range of meaning throughout the given Testament.

3. Theological Wordbooks

Along with lexicons, you should be aware of some extremely helpful word study dictionaries, also known as theological wordbooks. These multi-volume tools, most of which are available for your electronic Bible software, include articles that survey all major uses of a given term throughout Scripture and also often comment on its use outside the Bible. The best theological wordbook for Old Testament studies is VanGemeren’s five-volume New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis (Zondervan, 1997). The essays are usually of manageable size for sermon preparation, and all are accessible through G/K numbers (a Strong’s to G/K number index is in the back of volume 5). Each study synthesizes a given Hebrew term’s usage throughout the entire Old Testament, and most entries set theological trajectories into the New Testament. This is a resource well worth having in your library. A similar volume, though older and smaller, is Harris, Archer, and Waltke’s Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (Moody, 1980). As above, this tool is tied to Strong’s numbers, making it accessible to those who don’t know the biblical languages. All of us need these kinds of tools. However, they are best used to offer initial perspective and/or compare with word and concept studies that we have already done on our own.

Principles for Doing Word Studies

Certain principles help interpreters responsibly do word studies. Sadly, those studying the Bible often err in establishing a word’s meaning by failing to heed three principles.

1. The history and makeup of a word are not a reliable guide to meaning.

- Past usage is not necessarily equivalent to current usage: The original meaning (etymology) of a word is an unreliable guide to its contemporary use. For example, “awful” in English previously expressed reverence (i.e., full of awe), but today it most commonly means something that is very bad or unpleasant. Similarly, while the Hebrew zāqān (“beard”) was originally related to the idea of being old (cf. the Qal verb zqn [“grow old”]; the adjective zāqēn [“old”]), this connection is not necessarily apparent in Scripture.

- Similar roots do not necessarily have similar meanings: Verbs and nouns that share the same root do not always share the same semantic meaning in Hebrew or English. An example in English is the verb “undertake” versus the noun “undertaker.” The latter has a much more limited range of usage. Also, the noun “adult” has no direct link with the noun “adultery.” In Hebrew, the noun miḏbār (“wilderness”) bears no connection in meaning to the Piel verb dibēr (“to speak”).

- Comparative languages are unreliable guides: Similar vocabulary from a related language (i.e., a cognate) is an unreliable guide to meaning. For example, in English, we cannot determine the meaning of “dynamite” from the Greek cognate dynamis (“power”). There are times when we are forced to look at cognates to assess the possible meaning of a term, but we must recognize any conclusion as tentative.

2. Usage in context determines meaning.

- Context is king: The historical and literary context is always determinative for a word’s meaning, most significantly when several different meanings exist for a given word. In English, “minutes” can be parts of an hour or notes from a meeting. Context alone clarifies which meaning is in use. Likewise, biblical Hebrew contains many words with multiple meanings. The Hebrew rûaḥ can mean either “wind” or “spirit,” depending on the context, and interpreters are not at liberty to choose whichever meaning they want. The author of Scripture clarifies his intended meaning from the context.

- Look out for idioms: One must consider whether combinations of verb + preposition take on special meanings. In English, the idiomatic expression “just a minute” refers to an undefined period and could not be applied to, for example, the statement, “Class will be fifty minutes long.” So too, in the Hebrew phrase “the day of Yahweh,” the term “day” does not refer to a twenty-four hour period, even though this is clearly the meaning of “day” in other contexts.

- Assigned meanings must not be too limited: While context is paramount for determining meaning, the interpreter must construe a term’s meaning broadly enough to fit all appropriate contexts (except in cases of idiomatic or technical usage). For example, in English, we should not define the verb “swim” by a particular arm stroke. Numerous arm strokes would qualify for “swimming.” Accordingly, in biblical Hebrew, the Qal verb of the root br’ (“create”) cannot mean “create out of nothing,” for this meaning cannot apply to Genesis 5:1, where we are told that God “created” man (cf. Gen 2:7).

3. Authorial, historical, geographical, and formal correspondences matter when determining meaning.

- Authorial correspondence: A given author’s use of a term elsewhere should bear greater influence in your assessment than the uses of other authors. Also, the comparative significance increases all the more when an author uses the term in the same book. For example, if you’re considering the meaning of the feminine noun “righteousness” (ṣeḏāqâ) in Genesis 15:6, the eight other occurrences in the Law of Moses should bear a priority in your analysis.

- Historical correspondence: Because languages evolve over time, comparing word-usage of authors living at the same time is normally more helpful than comparing authors from different historical eras. As such, if you are working through Micah 5:2 and want to better grasp the meaning of the term for “ruler” (Hebrew Qal participle môšēl) , the eleven occurences of the same form in Isaiah would be helpful, seeing as the two prophets were serving at the same time. Importantly, when an author is drawing his language from previous Scripture, the earlier biblical usage often controls the later meaning.

- Geographical correspondence: As in English, classical Hebrew had its own dialects, and these geographical distinctions could influence not only intonation (e.g., Judg 12:5–6) but also word usage and meanings. As such, considering whether you are reading a northern or southern prophet could influence your word study.

- Generic or formal correspondence: Genres may prefer certain word meanings over others. For example, if you are working through Psalm 33, a psalm of praise, the term “shout” (trû‘â) is less likely a “war cry” (Jer 4:19) and more likely a “shout of joy”: “Sing to him a new song; play skillfully on the strings, with loud shouts” (Ps 33:3).

How to Do a Word or Concept Study

Because effective communication depends on the meaning of words, word and conceptstudies are a vital part of the interpretive enterprise. Before turning immediately to secondary sources like a lexicon or theological wordbook that give you the results of word and concept studies that other people have done, you should always consider doing a word study yourself. The process of personal discovery can be both edifying and rewarding. It will also help you better recognize careful research when you find it.

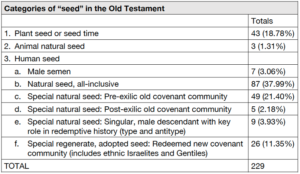

1. Choose a Hebrew word or phrase to study: Consider words or phrases that are theologically significant, puzzling, figurative in meaning, repeated, or infrequent. In the past, I chose the Hebrew word zera‘ (“seed, offspring”; S 2233; G/K 2446).

2. Discover the range of meaning for your Hebrew word (external data): Generate a list of texts from a Hebrew-based concordance, categorize the meanings, and catalog and asses the data. For my “seed” word study, I discerned eight separate meanings.

In my study, I noted a number of features like the following:

- When “seed” refers to humans, some occurrences are not all-inclusive but restrictive, pertaining to a certain group of “offspring” within a greater unit. Hence, while Ishmael was Abraham’s “seed” (Gen 21:13), he was not among the “offspring” who would inherit the promised land (12:7; 17:20). Furthermore, a single, male “seed” of the woman and of Abraham would overcome Adam’s curse and bring blessing to the world (3:15; 22:17–18).

- When “seed” refers to humans it almost always refers to natural children. Thus, Eliezer of Damascus was Abram’s heir but not his “seed” (Gen 15:2–3), whereas Moab and Bene-ammi were the biological “offspring” of Lot’s daughters (19:32, 34, 37–38). The only exception to human “seed” referring to physical descent comes in Old Testament promise texts that address the makeup of the new covenant community (e.g., Isa 53:10; 54:3; 59:21).

- The New Testament refers to Jesus as the “seed” of Abraham (Gal 3:16) and emphasizes that all who identify with him by faith equally become Abraham’s “offspring” and full heirs of the promises (3:29).

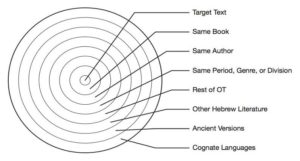

As a final step in your external assessment, it is normally good to expand your assessment to include the concept. As highlighted in “Principles for Doing Word and Concept Studies” above, there are different levels of correspondences or contexts that we need to keep in mind when doing word and concept studies. The chart below reflects these different levels.

As you move out from the center, you increase the number of possible contexts for your word. Because immediate context is always most determinative for meaning, a high number of examples toward the center may allow the busy teacher less of a need to extend the search outward. Nevertheless, a thorough study requires this, and the investment can be massively rewarding.

3. Determine the meaning of your Hebrew word in the target text (internal data): Do this by asking questions like the following: What does the immediate literary context clarify about your word’s meaning? Does your author use the same term elsewhere in the book? Do other Old Testament authors appropriate the term in similar settings or when addressing similar issues? Does the New Testament quote or allude to your text in a clarifying way? Does your author use the word in a different manner from the way others do?

Once you decide on the meaning of the word in your passage, verify your decision against the most important lexicons and theological wordbooks. Remember: There is no substitute for performing your own word study before seeing what others have said. Only with your own research in hand will you be able to evaluate others’ claims and to evaluate your own decisions against theirs.