When interpreting Scripture, we observe carefully by considering how a passage is communicated. We have already established the literary units and text hierarchy (step 2) and assessed clause and text grammar (step 5). So, we are ready to finish tracing the literary argument and to create a message-driven outline that is tied to the passage’s main point. “Argument-tracing” is step 6 in understanding and apply the Old Testament. Perhaps more than any other step in the exegetical process, this one helps us grasp a passage’s message. In this post, I will show how to trace the argument of a passage by using an argument-diagram.

Create an Argument Diagram

To understand a passage’s structure, we must evaluate the relationship of every proposition, clause, and larger text unit. This type of appraisal is most natural when the argument is chronologically or logically linear (A-B-C-D-E) as opposed to parallel (A-B-C-A’-B’-C’) or symmetric (A-B-C-B’-A’). Regardless, in each structure, every proposition contributes in its own way to developing the passage’s main idea. The relationships between propositions can either be coordinate or subordinate.

- Coordinate relationships are those that stand side-by-side. These elements could operate independently in series, in progression pointing to a climax, as alternate possibilities of a given situation, or as both true or both

- Subordinate relationships always have a main clause or text unit and then another that either restates, stands distinct from, or stands contrary to the main clause or text.

a. Restatement exists:

i. Where a stated action is followed by the manner for fulfilling that action,

ii. Where a comparison between two or more entities exists,

iii. Where the same thing is stated both negatively and positively,

iv. Where there is a question and an answer,

v. Where an idea is then explained

vi. Where a general statement is then specified, or

vii. Where a fact is then interpreted.

b. Distinct statements are evident:

i. Where one statement provides a ground or reason for another statement,

ii. Where one statement draws an inference from another.

iii. Where a single statement bilaterally grounds two different statements that frame it,

iv. Where there is an action and its result or an action and its purpose,

v. Where there is a condition for meeting a greater end,

vi. Where there is a specific temporal or locative marker, or

vii. Where anticipation through promise is accompanied by its fulfillment.

c. Contrary statements exist:

i. Where a concessive relationship is marked through a term like “although,” or

ii. Where a stated situation is followed by a response.

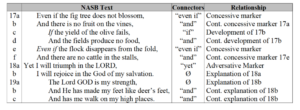

The following chart further clarifies these relationships and uses abbreviations or symbols to represent each.

All of these relationships are helpfully defined and overviewed at https://BibleArc.com. This is one of the best online-resources for personal Bible-study, and it’s my favorite tool for doing the actual brain-work of analyzing a passage’s thought-flow and propositional relationships. Here you can create a text-hierarchy through the “phrasing” module. Then, in the “discourse” module, you can identify the logical relationships of the various parts of your passage through “arcing” or “bracketing.”

Five Ways Arcing or Bracketing Assist Interpretation

The process of arcing or bracketing a passage assists our interpretation in at least five ways:

- It pushes us to recognize that the Bible presents profound and often complex arguments and not bullet points of unrelated truths;

- It forces us to take every connecting word seriously;

- It helps us to ensure that we do not leave any clause or proposition unexamined;

- It causes us to ask many questions that we may have otherwise not considered;

- It moves us to the main point of the passage.

Naturally, the best way to be certain you are tracing an Old Testament argument correctly is to use the Hebrew (or Aramaic), but a form-equivalent translation like the New American Standard Bible (NASB) works very well. As an example of the approach in English, let’s consider Habakkuk 3:17–19. These verses represent one of the great Old Testament expressions of persevering faith and hope for the age of the new covenant. I want to walk through my text hierarchy, and then we will track the logical relationships through an arc and bracket. The translation here is my own.

Text-Hierarchy of Habakkuk 3:17–19

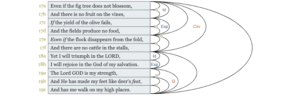

Reading the translation, you can see that the passage has two parts––the concessive protasis beginning with “even if” in verse 17, and the adversative apodosis starting in verse 18 with the explicit inference particle “then” and the first common singular pronoun “I.” The protasis by nature modifies the apodosis, so I have indented 17a–f to the right. The protasis itself has two parts: agricultural devastation in 17a–d and the ruin of the livestock in 17ef. The apodosis opens in 18a with a statement, “Yet I will triumph in the LORD,” which is then explained in 18b, “I will rejoice in the God of my salvation.” Asyndeton (i.e., lack of a connector) marks the explanation. Then what follows in verse 19 is a further inner-paragraph comment, also signaled by asyndeton, which appears to express the reason why Habakkuk commits to celebrate his God––he will do so because “The Lord GOD is my strength” (19a), and because God has empowered him to rise above his adversities through faith (19bc).

With this basic thought-flow in hand, let us now create an argument-diagram, considering the logical relationships evident in the text. Below I use what is called “arcing” but an equivalent tool is “bracketing.” Look back at the above chart to identify all the abbreviations.

Arc of Habakkuk 3:17–19

First, we must distinguish the concessive protasis in 17a–f (signaled by “Even if” in 17a) from the adversative apodosis in 18a–19c (signaled by “Yet”). I use the symbol “Csv” to mark the Concessive nature of the protasis. The concessive unit distinguishes between God’s curse on crops in 17a–d and his curse on domesticated animals in 17e–f, so I put arcs over the various sections. Note that each unit bears a parallel structure: a clause with action verb in 17a (“blossom”) and 17e (“disappears”) is followed by an existential clause beginning with the negative expression “there is not” in 17b and 17f. These two groupings are coordinate and interchangeable, so I mark the relationship as Series with the symbol “S.” Within the first of these units, I have also treated 17cd as an Explication (Exp) of the Idea (Id) presented in 17ab. The second pair of clauses build on the content of the initial two clauses, developing the concept of agricultural devastation. We could rephrase it, “Even if the fig tree does not blossom, and there is no fruit on the vines––that is, if the yield of the olive fails, and the fields produce no food.”

Coming to the adversative apodosis (i.e., “Yet” clause) in verses 18–19, we begin with an Idea-Explanation (Id/Exp) in 18ab. After declaring, “Yet I will triumph in the LORD,” Habakkuk clarifies that what he means is, “I will rejoice in the God of my salvation.” The explanation is signaled by asyndeton or lack of connector (Ø).

What follows in verse 19 unpacks further why the prophet will rejoice in God, and even though there is not a formal causal conjunction like “because” or “for,” the relationship between verses 18 and 19 appears to be a Ground [G]: “Because the Lord GOD is my strength and empowers me to rise above my challenges, therefore I will rejoice in the God of my salvation.” O, that we would continue to savor our Savior amid times of testing (Matthew 5:11–12; Romans 5:3; James 1:2)! Habakkuk’s last two clauses are tied together thematically and appear to express a Progression [P]: God first makes Habakkuk’s feet like the deer’s and then moves him to walk in the heights.

Some of the logical relationships that I identified when doing my text-hierarchy, I have now been able to concretize and display through arcing the passage. I hope that you can begin to see the benefit of identifying the coordinate and subordinate relationships. Engaging in arcing or bracketing forces us to ask all the right questions and allows us to visualize in an instant the way all the parts of a text relate to each other.

Main Idea and Exegetical Outline of Habakkuk 3:17–19

When a passage has a two-part syntactic construction as in Habakkuk 3:17–19, the weight of the passage’s meaning always falls on the apodosis side. These verses, therefore, seek to motivate believers to follow Habakkuk in rejoicing in his saving God, even when tasting the impact of covenant curse. Every believer should rejoice in the saving God amid trial because the Lord is both able and committed to strengthen and sustain. This is the main idea of Habakkuk 3:17–19. I outline the flow of thought as follows:

I. The Cursed Context for a Believers Joy in the Saving God (v. 17)

a. Lack of earthly provision: Crop devastation (v. 17a–d)

b. Lack of earthly provision: Livestock devastation (v. 17e–f)

II. The Believer’s Declaration of Sustained Joy in the Saving God (vv. 18–19)

a. The assertation of joy in the saving God (v. 18)

b. The basis of joy in the saving God: His ability and commitment to strengthen and sustain (v. 19)